|

|

The dynamics of the wholesale telecoms market are in a state of flux. The industry constantly strives to better its offerings; and wholesalers are turning with increasing regularity to partnerships with strategic competitors to enable them to do so. Driven by declining margins and an occasionally urgent need to reduce capital expenditure, a problem shared can indeed be a problem halved.

But every telco willing to speak about partnership arrangements stresses that their relationship is “unique.” As Michel Guyot, president of global voice solutions at Tata Communications, says: “There is no such thing as a one-size fits all partnership.” Each relationship is regarded by the parties involved as a hard fought and creative response to their individual pressures and circumstances. But there are, of course, certain commonalities and benefits. The most obvious one is money. Acquisition finance has become increasingly difficult to come by, and most telcos are used to balancing the need to control costs against the demands of investment in equipment, networks and development. Steven Hartley, principal analyst at Ovum, comments: “If the top line isn’t going to grow, it’s time to think about the bottom line and how we can strip costs out.”

Capital expenditure is particularly heavy when telcos deploy new technologies such as LTE. As independent analyst Derek Kerton points out: “There can be low utilisation in the early phases. It’s incredibly expensive to build a network for the first 500 people who use it.” Sharing that initial investment with a competitor is a practical solution to a short-term problem, even if businesses view their longer-term positioning differently.

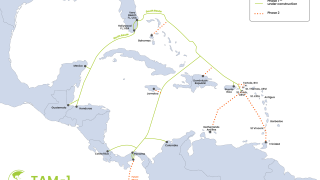

The solution isn’t new. Nearly a decade ago Bell Canada, with strong network coverage in east Canada, signed an “enhanced reciprocal agreement” with TELUS, which had experience in western Canada. The agreement aimed to expand access to digital voice and data services, bringing competition to rural areas, and saving the two parties around $500 million capex during the 10-year agreement. Consortia to jointly build and operate subsea cables have become almost the norm, and collaboration is common through standards bodies such as the GSM Association and Metro Ethernet Forum.

Mark Robinson, senior associate at international law firm Herbert Smith, has worked on a number of commercial contracts between telcos, and refers to “interparty working” as not uncommon, despite a historic reluctance for direct competitors to come together. But there has been an acceleration in recent months, with a number of major strategic alliances and joint ventures. Hartley explains, “It’s about finding synergies and exploiting them. You can probably throw out the old telco rulebook, which is that you own and operate your own network and you control everything from end to end.”

Overcoming competition

The creation of Everything Everywhere, a 50:50 joint venture between Orange and T-Mobile, is a classic example. Previously, the companies held the third and fourth positions in the UK mobile market, behind O2 and Vodafone. The UK has very high penetration levels and is nearing saturation. “The logical assumption was that one would buy the other,” says Hartley. “But neither wanted to exit the market. Instead, they said, ‘No, hang on a minute. Let’s try and merge together.’”

From a wholesale perspective, the merger created a business with a stronger, more powerful network. First outlined in September 2009 and cleared by the EU Commission in March 2010, the alliance created a joint venture company which claims synergies with a value in excess of €4 billion and a combined customer base of around 29.5 million, making it number one in the UK mobile market. The partners have benefitted from wider, deeper coverage, especially in key urban areas. “That scale allows us to do some interesting things,” says Marc Overton, VP of wholesale, Everything Everywhere. “It’s about having the most efficient and effective network and backbone.”

Everything Everywhere has shaken up the UK mobile market. But while those involved in such partnerships talk positively, there is often a note of caution. Overton emphasises that all such alliances must be considered “on a case by case basis.” Nor should the effort involved in creating a single business from two be underestimated. Staff, customers and end users all require re-education. Employees with a long history in one of the partnered organisations have a natural allegiance to their former employer. And although Orange and T-Mobile have partnered, the two businesses will continue to trade and compete under their individual brands for at least 18 months, while a strategic review about branding and identity takes place. “We have spent a lot of time with the teams,” said Overton, “immersing them in what Everything Everywhere is, explaining our cultures and our behaviours, and the strategy of the company going forward.”

Competition plays a huge role in managing the successful outcome of such a partnership. Guyot summarises the problem: “We are suppliers, customers and competitors all at the same time.” But the real difficulties can be found on the regulatory front. Exclusivity arrangements can be labelled anti-competitive, and businesses are often required to go to some lengths to prove that joint ventures will not have a negative effect on the market and end users – not always successfully. In April 2010, a proposed merger of Orange with Swiss telecommunications firm Sunrise was blocked by ComCo, the Swiss competition commission. ComCo justified its decision to Reuters, claiming that: “These two companies would have been in a collective dominant position which risked eliminating competition.”

“The EU has made it clear that it’s going to champion the cause of competition,” says Hartley. Decisions have ensured that smaller players have a chance, allowing virtual operators into networks and creating conditions that encourage operators into the market. The penalties for breaching competition law can be severe. Robinson says, “It’s very important to get this right, otherwise companies can face fines of 10% of their turnover, as well as all sorts of claims from third parties.”

Everything? Everywhere?

The situation can rapidly become complicated, however, as can be seen even with the Everything Everywhere alliance. Before entering the joint venture with Orange, T-Mobile had negotiated an earlier partnership with 3 UK, in another 50:50 joint venture company called Mobile Broadband Network Limited (MBNL). The MBNL consolidation agreement was signed in 2007, to manage and deliver the combined 3G access networks of the two companies; it was at the time the world’s largest known active 3G network consolidation. The problem was that the agreement was still in effect when T-Mobile began negotiations with Orange.

A number of concessions between the three parties were negotiated to prevent any claims of anti-competitiveness. Orange joined the 3G network, contributing several thousand base stations for network- sharing purposes. MBNL is now a 50:50 joint venture between 3 UK and Everything Everywhere. “We’re also 3 UK’s roaming partner,” says Overton, “so there’s a close co-operation between us to develop this future supernetwork.” The venture has created a network of breadth and depth, but against a complicated backdrop. As Robinson explains, “It’s a joint venture on a joint venture, which potentially makes life very difficult.” 3 UK also had concerns about radio spectrum, issuing a statement in 2010 while the merger was under EC consideration: “The proposed merger could lead to a concentration of 84% of the nation’s 1800MHz radio spectrum in the hands of a single company.” One of the pre-conditions for the eventual joint venture was Orange and T-Mobile’s agreement to a spectrum divestment, handing back 2x15MHz of their 1800MHz spectrum, 25% of their total 1800MHz holdings. The story doesn’t stop there, though. Virgin Mobile is a wholesale customer of T-Mobile, becoming the UK’s first MVNO in 1999. As a result, its customers have also been able to access the supernetwork. “If you follow the logical chain of events,” said Hartley, “you get to the point of having just one network.”

Leaving nothing to chance

While a single all-inclusive supernetwork might seem far-fetched, the concept of the neutral host is definitely being tested. Arquiva, a broadcast and media company, owns the UK terrestrial broadcast network as well as media hubs in Los Angeles, Washington and Paris. It is conducting a trial network for LTE with Alcatel-Lucent in the Preseli Mountains in Wales which seeks to demonstrate the economic and technical viability of a neutral-host wireless network, extending broadband internet services to areas with no broadband coverage and those with speeds below 2Mbps. Arquiva’s neutral-host network solution would offer wholesale access to all service providers and new entrants.

As provision of 4G and LTE increases, the concept of a national backbone is starting to gain momentum. In Sweden, regulations have actively encouraged network sharing, leading Telenor Sweden and Tele2 Sweden to jointly build a 4G network. Instead of being driven to reach commercial agreements over time, they started out with the premise.

In September 2010, Telenor also signed a partnership agreement with Telefonica to support the requirements of their multinational customers in each other’s markets, across 22 countries. Although he believes a relationship like this evolves over time, Terje Bjørnsen, VP, Nordic accounts at Telenor Nordic, thinks that the more the two parties can agree upfront the better: “What are the terms, conditions and processes? The more you can solve these questions, the easier it is to implement the agreement.” Within contracts, protection clauses are common, requiring providers to meet service delivery targets, meet technological requirements, respond to the evolution of the market, and so on.

Of course, the agreement must also establish terms for its conclusion. Most partnerships are established for a fixed period, when they must either conclude or be renewed. Before Telenor entered its agreement with Telefonica, it had held a partnership with Vodafone. Bjørnsen explains, “We were considering whether to renew that agreement, when Telefonica needed a partner in the Nordic region. We were not in strong competition with Vodafone, but we had a few points where we had a conflict of interest, which could make collaboration more difficult.” The complementary geographical footprints enjoyed by Telenor and Telefonica eventually drove Telenor to conclude one partnership and begin afresh.

However stringently planned the partnership may be, some do not end well. “In a joint venture, there are a number of mechanisms that can be used for exit,” says Robinson. “They range from liquidating the company or buying out each other, to Russian roulette, where both parties go into auction.” Bjørnsen says this is “the flip side of the coin” when going into partnership: “You create a value proposition for your customers; if you succeed, they will believe in it. If you need to terminate that partnership, there will always be difficulties. But it depends on that alternative, and how you manage expectations.”

Whether opting for acquisition or partnership, major considerations must be taken into account. As Robinson says: “Joint venture probably gives you more flexibility than acquisition, but there’s a little less transparency. And a lot of the same issues do come up: exit, regulations, competition. You have to tackle these whichever way you’re going.” Bringing simultaneously more freedom and more complexity, it will be interesting to watch how the telecoms world responds.

Recent activity |

One of the significant advantages of joint venture and partnership agreements – when they are successful – is the flexibility available to both parties to develop expertise and expand into new areas. Here are just some of the bigger partnerships which have been reached, and concluded, over the last few months:

|

Tata Communication and BT |

In 2009, Tata Communications and BT signed a five-year global strategic voice services agreement. Tata Communications has become BT’s primary supplier of international direct dial and voice termination services outside BT’s footprint countries. In return, BT has become Tata Communications’ main distribution channel for its IDD traffic into the UK. “To be successful, you need a high level of focus on your core contingency,” says Michel Guyot, president of global voice solutions at Tata Communications. “We compared costs and strength, and it made sense for BT to give their traffic to Tata Communications. We had a salesforce in the UK, but BT is much better positioned than us to do that, so we gave them our UK customers. That’s partnership: by pooling our traffic, we can obtain better termination costs with various carriers around the world. We try to enhance the relationship by providing BT with service management tools and giving them access to our system. In real time, they can see the traffic that they generate and terminate, their cost and profitability.” Since the BT agreement, Tata has gone one to sign at least six similar, if smaller scale, partnerships, including gotalk in Australia and Videotron in Canada, as part of its global partner programme.

|