How fast is fast enough? It’s a question that banks and financial institutions ask themselves – and their bandwidth providers – almost daily. It is borne of a need to retain a competitive edge in a rapidly evolving industry where computer-driven trading strategies can generate millions of low-risk dollars at, quite literally, the speed of light.

Around the outskirts of a stretch of protected forest on England’s south coast, network engineers from several major bandwidth providers are searching for clues that might help them devise a short cut through the woodland. The picturesque glade lies right in the middle of the London-to-Frankfurt pathway, the busiest route in the world for financial traffic; they hope to slice hundreds of microseconds off the speed at which buy and sell orders course between the two financial centres by shortening the route through the trees.

If that all sounds like some bizarre take on an old-fashioned fairy tale, consider this: fibre providers work on the basis that they can shave one microsecond (one thousandth of a millisecond) off the latency of a route every time they shorten the fibre cable by just 100m.

‘High-frequency’ trading

Perhaps even more remarkable than the dozens of network surveyors beating a trail through the English countryside, is the fact that banking institutions are not only sufficiently familiar with the physics of the speed of light as to demand this of their providers, but that they are also willing to pay a big enough premium for connectivity – in many cases well over double that of other enterprise customers – to make the search cost effective.

As David Selby, VP of product and strategy at euNetworks explains, it was not always so: “If you go back five years, it was difficult to get through the door of a top-flight investment bank to chat about their telecoms needs, let alone get to their procurement guys to talk about budgets.”

All that has changed in the last two years, as computer-driven trading technologies have risen to the fore. These take many different forms but typically rely on an array of computer algorithms that exploit minute pricing irregularities across a range of interlinked stocks, bonds and derivatives, triggering rapid buy and sell orders that work their way through the markets, long before the human eye even notices them in the first place.

These are not the dice-rolling punts that precipitated the credit crisis, but rather low-risk high-volume trades that oil the wheels of the financial markets. According to the New York Stock Exchange, such so-called ‘high frequency’ trading strategies typically account for anything up to 80% of total trading volumes on Wall Street, generating huge pools of liquidity that enable mainstream pension funds to make longer-term investment decisions.

Speed is necessarily of the essence, not only to ensure that you can complete the trade in the first place but also to enable you to get there ahead of the competition. And in this race to become the fastest, the banks have not only become experts in fibre optics but they have also willingly unbundled the way in which they buy telecoms services in order to root out specialist providers who best understand the need to drive latency lower.

As Selby explains: “We are dealing with a lot of very smart people who are very focussed on generating trading profits. These are not people who shy away from complex technical issues and it is not uncommon for us to be questioned very robustly on our assumptions on the speed of light through our fibre as it relates to the refractive index.”

Shortening route distance

It is widely assumed within the industry that route distance accounts for as much as 92% of latency; the remainder being made up by the type of laser equipment installed at either end of the circuit and the quality of light travelling down the fibre. The relentless push to shorten routes between key financial centres, dubbed by some as the ‘race to zero’, clearly has some way to go. In the two years that banks have specifically targeted latency as a key criterion in their connectivity needs, network providers have chopped around 150km off the route between London to Frankfurt, equivalent to shaving around 1.5 milliseconds off the round-trip delay.

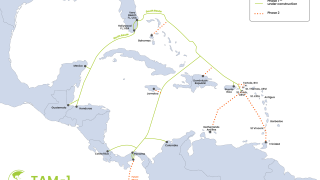

Hibernia Atlantic, meanwhile, is investing more than $250 million in a new transatlantic submarine cable. “We are building Project Express to directly respond to the financial industry’s need for lowest latency connections,” states Mike Saunders, VP of business development, Hibernia Atlantic. “The new fibre-optic cable will offer the fastest speeds yet between New York and London, with sub-60 millisecond latency – a first in transatlantic cable history. It’s also the first time in over 10 years that a true trans-atlantic crossing has been attempted.” Hibernia says that the new cable, part of a purpose-built global fibre network created to meet the demanding performance and reliability requirements of the financial community, will help trading firms and exchanges interconnect faster than ever.

“We’ve seen a significant transformation in the product set being sold,” says Selby. “Around two years ago, when latency was perhaps less well understood, the banking sector would typically look for a Layer 2 switched Ethernet service with a 100Mbps hand off.” This created challenges in itself – Layer 2 services would typically be protected and therefore subject to rerouting with a generic. Now the fast-trade sector has moved to a dedicated optical solution using fixed point-to-point connectivity over DWDM technologies.”

The crucial point here is that while the service delivers very dependable levels of latency, the connection itself is unprotected. “Most ring architectures in western Europe are at least 2,500km long, so you would be looking at possibly tripling current levels of latency in order to offer protected connectivity,” explains Selby. While that’s clearly not an option for banking institutions, they have had to embrace the operational difficulties of dealing with unprotected networks: “In the early days they didn’t necessarily design networks with redundancy but now they typically buy multiple services from multiple carriers,” Selby adds.

Latency guarantees

euNetworks recently gave its own shareholders an optimistic update in which it confirmed that it had signed up 22 new banks to its London-Frankfurt route in the third quarter alone. The firm also expanded its network with a new service from London to Stockholm, cutting incumbent latency levels by up to 12%. Of course, the beauty of a dedicated fibre network is that latency guarantees can be easily embedded into service level agreements (SLAs): provided there are no problems with the equipment at either end of the circuit, and assuming that the fibre does not break, it is possible to wrap a very precise guarantee into a service contract.

“When the data flowing down these routes is so business critical to the customer, you tend to find that a lot of effort goes into the pre-sales discussions,” says Dave Cribbs, VTLWavenet’s SVP for marketing. “The way you measure latency, the points on the network from which you take the measure, even the type of traffic that you use to test it, can all have a bearing on the end number – as indeed can the type of fibre that is deployed.”

Tony Moulange, senior business development manager in COLT’s financial services division, agrees. COLT services 24 of Europe’s 25 largest hedge funds and Moulange’s team are used to dealing with ever more exacting demands: “Financial institutions are extremely knowledgeable – they want to put their own measurement tools on each end of the circuit and will bring in specialist consultants to test the network. It’s not uncommon for them to want to know exactly on which side of a particular street the fibre runs,” he says.

COLT’s experiences are echoed by other providers: “On the one hand, the banks tend to be very resource rich,” explains one senior product developer with detailed knowledge of the financial services sector. “At a meeting, you will always be outnumbered by people who can match you in terms of technological expertise, so things can get done pretty quickly. But these guys are perceived by their companies to be cost centres and they carry with them a huge amount of paranoia in terms of delivering the very fastest connectivity they can to their traders.”

“The fact that such huge sums are travelling down the fibre makes a big difference,” adds Jonathan Wright, commercial director at Interoute. “You need to know how the fibre is routed, how it interplays with their back-up provisions and, where you’ve had to buy little pieces of network from third-party providers to lower your latency number, how your SLAs interplay with one another.”

Ultimately, the risks to each provider are pretty much the same and there is a strong degree of confidence among providers who work with one another along key routes: “Clearly, if you have six or seven providers on a route such as London to Frankfurt and there’s a fault, there’s going to be a lot of phoning around and you are unlikely to get a uniformity of service. But that’s a price the banks are prepared to pay. They will always migrate to the fastest routes and prepare to switch when there’s a problem,” explains the industry insider.

Providers are also comfortable with the risks. James Heard of Level 3 explains: “The problem we have is not so much how we guarantee the quality of any fibre we lease – we can test that rigorously using our own equipment – but rather how we source that fibre in the first place. While we own and manage the vast majority of our network, we are constantly looking for incremental latency improvements by digging or utilising appropriate partners.” In Europe, Level 3’s corporate customer base is rapidly growing as more enterprises tap into the benefits of low latency.

COLT, one of the largest network providers to the financial sector, will now guarantee latency on the route to two decimal places, quoting a headline figure of just 4.22 milliseconds. But future improvements of this magnitude are clearly going to be harder to come by and the law of diminishing returns is beginning to cast a shadow. “Obviously there is a theoretical latency number that you’re striving to reach for any particular route – and you get that by drawing a straight line,” explains Wright. But the chances of getting anywhere near it are pretty slim because of issues concerning rights of way,” he says. “When it comes to London to Frankfurt, we are fast approaching the point where, to make any significant inroads, you’re going to have to do some substantial digging. That said, our network teams are always on the lookout for more obscure network providers that might help cut another chunk off the route and there are unique players who might have fibre such as educational facilities or even the military. There’s still a lot of piecework to do to make the route better,” he says.

“The banks expect annual improvements in latency of 10% or more,” says one provider. “With the exception of London, where the routes between various exchanges are so short that pretty much any improvement in latency will win you a deal, those numbers are going to have to come down,” the provider adds.

Further clouding the race to zero is the need for banks to have a reliable back-up route to hand. Institutions want to avoid a network event such as a break in the fibre leaving them with an open trading exposure so the need to line up diverse routes is fast becoming a top priority.

Diversity meets latency

The trick, according to VTLWavenet’s Dave Cribbs, is to strike a plausible balance between diversity and the need for low latency: “It’s a bit like asking a parent of twins which one they like best – you just can’t make that choice. Obviously the financial sector is principally driven by the need for ultra-fast connectivity. If you have the fastest route in the market but that fibre route passes over another fibre that the customer already uses, it’s not a given that he will sign up to you. Around 35% of our network is diverse to other carriers in Europe, so we pick up business in circumstances where we may not necessarily have the very lowest latency levels in the market,” he adds. Unlike many providers, VTLWavenet does not use the Channel Tunnel, with fibre running instead through Lowestoft to the east of England and Polegate on the south coast.

Opportunities for network providers in the financial services sector might be capped by the extent to which routes can be shortened, but there are new opportunities to exploit for the nimble footed: “There’s not a single bank or hedge fund in the world that doesn’t want to connect to big pools of liquidity. So the challenge for us is to anticipate where liquidity is moving, both in terms of geography and in terms of asset class,” explains Moulange.

There has already been a huge shift in high-frequency trading from over-the-counter derivatives to equities. Now, with regulators seeking to drive more and more trading onto recognised exchanges, huge pools of liquidity are set to develop in other financial markets – particularly foreign exchange, bonds and commodities. Similarly banks are looking to tap into burgeoning economies in the Middle East and Africa, as well as India. But rather than just migrating to new markets as and when they develop, COLT is also looking to develop its own liquidity hotspots. Plans are afoot to establish so-called ‘arbitrage centres’ where traders will be able to play a variety of asset classes across multiple exchanges on ultra-low-level latency networks in London, Frankfurt and Tokyo. The company declines to elaborate on the proposals and will not say what level of investment will be required.

Meanwhile, at Level 3, network engineers are seeking to roll out an ultra-low-latency service to other niche markets. “We believe it is possible to leverage our expertise to any sector where there is a need to trade, transact or exchange mission critical data at very high speeds,” explains Heard. Healthcare is an obvious case in point as the need to transfer images to off-site experts at very high speeds – and back again – is increasing with each swathe of reforms to the sector. Online gambling and gaming industries are also potential buyers of low-latency networks. “We talk about this a lot – pretty much every sector in the enterprise space is becoming more interested in low latency but how much of that is driven purely by wanting to offer a better user experience for, say, video teleconferencing, and how much is driven by the perception that the area is a cool subject, is pretty hard to say. All I would say, is that this is very much a journey and there’s very definitely more to come.”