“Wherever people live, broadband connectivity is the third or fourth thing they now require, after water and power,” believes Ian Douglas, managing director of the Telecoms Business Unit of Global Marine Systems, a major name in submarine fibre construction to all corners of the globe.

The result, says Douglas, is that the range of work commissioned from Global Marine has been growing steadily wider over the past year or two, and its extremities more unusual and rarefied, as the world’s remoter human outposts demand and receive their own direct global connectivity.

“We’ve done projects in Papua New Guinea and near the North Pole – neither of which we’d have dreamed of a few years ago,” he says. “It’s all driven by the fact that people with no broadband infrastructure have been used to getting what they want over satellite connections or microwave links, but that doesn’t cut the mustard any more. They are demanding full fibre-based access. They’ve seen the evidence for the effect that networks could have on their economies, and that’s where they want to go.”

From logistics to leadership

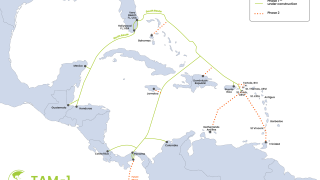

The further off the beaten path you go, the more difficult it becomes to deliver on people’s aspirations, explains Douglas. “There’s often a lack of the most basic facilities that you can take for granted in other regions,” he says. “We did a South American project recently with our partner Huawei to provide a link between Trinidad, Suriname and Guyana. Not only did we need to build the cable, but in Suriname we needed to build a landing station and install power where there had been none before. This is not a problem you’re going to face in Singapore or the UK. The effects since the system went live, I’m glad to say, have been fantastic. It has enabled so much.”

Cable construction logistics can be muddied by other factors than just extreme geography, points out Douglas: “In general, when building in undeveloped countries, you’re facing a much riskier political situation as well,” he explains. “You can get sudden leadership changes, as we saw in the Arab Spring. We’ve had projects delayed because of civil war.”

A project can founder, temporarily at least, on something as mundane as getting a new permit for a project out of an incoming regime, says Douglas: “A new government might well be inventing the whole permit procedure as they go,” he says. “Your existing permit, carefully applied for months before, has probably been issued by people who aren’t there any more. A permit is a critical feature of any job, and can put a whole project at risk.”

Danger points

On the darker side, says Douglas, there’s frequently the issue of the physical safety of employees and subcontractors to be factored in too: “There’s often much to be done to ensure the safety of our people, and we’ve had plenty of incidents that nobody wants to be involved in,” he says.

“Only recently we’ve had armed guards on one of our ships needing to discharge their weapons in the middle of the night to scare raiders off. You don’t get that in Porthcurno in Cornwall. Sometimes the stories make your hair curl – snake bites in the jungle, dead bodies washed up on the shore where you want to land your cable.”

Douglas recalls a recent danger point when a Global Marine ship had to be deliberately run aground to get a cable ashore: “At the other end of the scale, you’ve got cable laying to do in 6,000m of ocean,” he says.

A company like Global Marine, when faced with extreme or hostile conditions, has a responsibility not only to get round an array of possible physical problems, but to do so at the same time as showing a profit, and while coming in on budget on behalf of the cable investors that hired them. Risk costs money, and must therefore be measured as accurately as possible, and insured against.

“Risk analysis and insurance of these projects is not a new thing,” points out Douglas. “It’s just that there are a lot more places in the world where it’s now economic to build a cable, so in some respects there is a lot more risk to be analysed. To meet these needs we have to put our sophisticated risk assessment process to work. It involves a live document that follows the whole project from beginning to end, taking account of everything from health and safety to political and war risks. War risk insurance has to be obtained specially. It costs money every day you’re in the region, and depends on how valuable your ship and cargo are.”

Emerging economies

Global carrier Tata Communications has made a whole strategy out of serving under-developed countries with wholesale cable capacity, and thus is no stranger to working in extreme and challenging conditions. “We’re the largest operator of subsea cables in the world,” says Byron Clatterbuck, president of global carrier solutions with Tata Communications.

“When TGN Eurasia is completed, we’ll have cables that go right the way around the globe. Most growth is coming out of emerging economies, and that’s where we’re investing – India, Africa, Asia and the Middle East. The difficulties of these regions come out of the very fact that they’re emerging, and we’ve got plenty of experience in dealing with that.”

Clatterbuck explains that when opening up a new and potentially difficult market, the imperative of making a profit out of the venture is naturally an early concern.

“We’re all in this to make money, so the first question is always going to be: is there enough demand to make this profitable? Is there a market?” he says. He points out that it is not just the initial construction phase that must be accounted for when weighing up the profit and loss of working in challenging surroundings, but the subsequent maintenance overheads too.

“A recent Tata project saw us laying fibre between India and China, high up in a pass in the Himalayas,” he says. “That’s a lot trickier than anything subsea. The ground freezes in winter and it’s tough not only to lay cable, but to repair it when it’s faulty. When a network is built in an emerging market, you’ve got to maintain it where there may be other infrastructure – roads, transport, air links – still being constructed. Installing it is just the start. What happens when it breaks – in the Arctic or in the mountains?”

When it comes to subsea projects, deep water can present an obvious maintenance hazard, but it is near-shore work where the difficulties can really mount up, he says: “Most of a subsea cable is in international waters, so it’s only when it’s near land that you start having to worry about things like regulations and politics.”

Cables near a shoreline that is in commercial use by a number of other parties inevitably involves substantial diplomacy and major planning, says Clatterbuck: “In Korea we had to negotiate with seaweed farmers before we could land a cable, while in Japan we needed to reach a settlement with the fishing unions,” he recalls.

“There’s also the likelihood that you’ll be running across other pipelines for oil and gas, which means more negotiations and permission. All this complication means cost, some of which, like seaweed farmers, you can calculate easily up front. What you don’t want is unforeseen damage to something that you can’t afford to repair. Sometimes the unforeseen is political. Then you have other decisions to make. Do you want to send people into an area of conflict?”

Reviewing a long career, Clatterbuck doesn’t think there’s anything essentially new about taking on tough conditions in search of profitable opportunities: “I’ve been in infrastructure for 12 years, through booms and busts,” he says. “When I was with Level 3 back in 1999, laying cables around the Far East, the challenge there was that the inland fibre networks were just not there. How do you get terabit capacity from the shore into someone’s house so they can use it to look at the internet?”

What is different about the current era of global capacity, he believes, is the degree of added value that any new fibre project must bring to the market in order to compete with other transport options that would not have existed 10 years previously: “Are you providing a route away from known danger zones? Are you offering proper diversity, or extra low latency? We’ve got a good team in place to look at all these issues and mitigate all risks. The industry generally, I’m pleased to say, is smarter at planning cables, and takes a more mature attitude all round.”

Arctic conditions

If infrastructure is being planned for an under-served region where large open spaces with sparse populations must be negotiated, fibre is not always the answer.

When Norwegian incumbent Telenor wanted to connect the outlying Svalbard islands to its main network, it asked equipment vendor Huawei to come up with an appropriate unwired broadband solution to complement the sparse amount of fibre available. “The Svalbard islands are very isolated with fewer than 3,000 inhabitants,” explains Changmian Wang, wireless product manager for Huawei’s Telenor Business Unit, which was set up to deliver the project.

“Mobile broadband communication is the only way for most residents to keep contact with the outside world. For the locals, mobile broadband provides them with a very flexible way to access the internet. Svalbard is also a tourist centre and research centre, since it is so close to the North Pole. We identified LTE as the best way to provide all the visitors and researchers with better mobile broadband services.”

Since being awarded the contract to upgrade communications in the region to LTE in October 2009, Huawei has been swapping over existing 2G and 3G networks to the new standard.

“Some of the challenges have included the extreme Arctic climate, and the distance from the Norwegian mainland,” said Wang.

Wang says that, amazingly, the first telegraph tower built on Svalbard dates back to 1911. Now, he says, Huawei’s know how has brought it bang up to date again, 100 years on. “LTE is recognised as the fastest wireless network standard in history,” he says. “So with LTE launched in such a special place, it’s not hard to imagine the impact it will have. As a project, it was made more meaningful by the extremity of the location.”

Huawei, he says, will continue helping Telenor to deploy LTE in Norway’s remoter corners in the coming years: “LTE is a strategic project for Telenor, and the long-term plan is to use it to cover up to 97% of the population in Norway,” says Wang. “The main accomplishment of the LTE launch in the archipelago shows that wireless equipment is capable of optimal performance in even the harshest natural conditions.”

“Longyearbyen [in Svalbard] has changed radically during the year, and we have given the locals a better means of communication,” says Bjørn Amundsen, coverage director of Telenor. “We have upgraded base stations there, and now we want to make a closed test. We are interested in particular in seeing how a group of chosen users, who already have fibre connections with good capacity, make use of mobile broadband.”

As always, one price of progress is that the world shrinks to become a slightly smaller and more manageable place. Yesterday’s extreme hotspot filled with danger is tomorrow’s safe, even banal haven of prosperity.

How to measure danger

Consulting firm Datamonitor Research keeps a close watch on which parts of the world represent the biggest challenges to those looking to establish a hub for business, publishing the results in its Black Book of Outsourcing.

An annual ranking of the most dangerous outsourcing spots around the globe, as perceived by buyers of services and corporate development leaders, it is a way for outsourcing purchasers to judge where risk lies, and also how patterns of risk change.

On the most recent listing, Karachi in Pakistan, Medellin in Colombia and Juarez in Mexico were all awarded the highest score as bad places to turn to for outsourced services. This rating was due to their high levels of crime and corruption, the threat of terrorism and their wild currency fluctuations.

But Bogota in Colombia, voted most dangerous city for outsourcing in 2009, now ranks in the middle of the 160 outsourcing destinations included in the survey. So is this a vast improvement in short order and proof that with the right political leadership, a challenging and extreme environment can become an almost desirable one very speedily? Or is it smoke and mirrors?

“For Bogota, whose scores in the areas of local strife, corruption and organised crime, unstable currency and unprotected infrastructure improved in 2010, the rise in the rankings may be the result of a targeted public relations effort,” says Datamonitor research director Doug Brown. “Bogota conducted a message-focussed media campaign to separate itself as a safer city from the rest of Colombia and as a location with decreasing risk potential. Actual statistics say Bogota has made some noted improvements in areas which threaten business operations, but it’s difficult to say if this perception increase is the result of marketing or actual progress.”

Wally Swain, senior vice president with analyst firm the Yankee Group, based in Bogota, believes there is some hard truth behind the city’s apparent success story: “There’s a lot of opportunity now,” he says. “Colombian telecoms in particular have been a success story in the past few years. This is not the same country it was a few years ago, and it is proof that things can change.”