|

|

Over a decade ago, the former founder and board member at US exchange company Arbinet, Alex Mashinsky, met with a group of Enron executives.

During the meeting, he looked the group of hard-nosed traders in the eyes and told them, that while their idea to create a bandwidth exchange platform was interesting, “it was not going to be about data for the next 10 years, it was going to be about voice”.

The board ignored Mashinsky and told him in no uncertain terms that “there is an insurmountable amount of money in bandwidth trading”. The rest, as they say, is history.

Enron invested aggressively in bandwidth trading, and attempted to consolidate a market that had little belief their model would work. Enron’s hard-line approach quickly left its investors out of pocket, and the company eventually went bust.

Although his prediction proved correct, Mashinsky regrets voicing his concern to the Enron board. In the very same meeting he rejected a $100 million offer from Enron to acquire Arbinet. “Sometimes being right does not always bring you fruition,” he says. “But that’s life.”

Trading telecoms

Fast forward to 2012, and there is a CEO in town that believes the time is now right to re-establish the bandwidth exchange platform.

Andreas Hipp, CEO at Epsilon, has taken it upon himself to attempt to trade bandwidth again, and it has generated a host of opinions from old and new players in the market.

Although Epsilon Capacity Exchange (eCX) works a little differently to the platforms that were developed in the late nineties just before the famous telecoms bust of 2001, the same fundamentals are there.

eCX offers both buyers and sellers an online trading platform for SDH and Ethernet bandwidth services, incorporating a real-time inventory of routes, a pricing and trading engine and a capacity booking and reservation function.

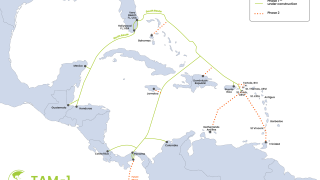

For Epsilon, it builds on a profitable business that is has worked on for a number of years, incorporating its global network exchange spanning across 60 PoPs worldwide. Hipp claims the idea and the development of the platform is really driven by the need to speed up a process that is dated, and can now be facilitated by a range of technological developments.

“We have built the infrastructure that Enron did not have 12 years ago,” says Hipp, who spent six months at Enron in 2001. “We identified that we had a lot of customers with idle capacity sitting on their networks which could have been because of big cable investments.”

In some ways Hipp’s reasoning to take the leap into bandwidth trading makes perfect sense. Over the past few years there has been substantial investment in subsea cable systems, which has left carriers and service providers alike with capacity they are not fully utilising.

“They approached us and asked if we needed any of that capacity, which we then tried to offload for the company, in essence becoming the middle man between carrier A and carrier B and as the transactions increased the solution was clear – it’s time to trade this capacity,” says Hipp.

Epsilon claims it had all the pre-requisites in place, and is only really tasked with establishing the front-end optimisation piece and operating the connectivity platform. Hipp does not want to get involved with price, contract terms or quality of service (QoS).

If the platform or the idea fails, as it has done in the past, “our business won’t be affected”, Hipp says defiantly. “There is an SLA to fall back on and it’s still the seller’s risk and obligation.”

Richard Elliott, now managing director at satellite communications provider Apollo, was one of the first pioneers of capacity trading. He co-founded Band-X back in 1997, and claims Band-X’s exchange concept was one of the first to hit the market, leading to numerous imitators including Arbinet, Enron and Dynergy.

Its developed platform originated in voice, and the company traded IP transit as a wholesale interconnection on the internet with a fixed and visible margin that also traded point-to-point circuits in a similar way to Epsilon. Elliott “takes his hat off to Epsilon”, and heralds the web-based front end developed by the company as “better than it ever has been”.

Leaving the past behind

Undoubtedly, the industry’s experience with the highly controversial Enron continues to leave a sour taste.

The fact is, however, that even Enron’s rivals failed in long-standing attempts to secure a highly scalable tradable platform for capacity. Jim Poole, general manager of global networks and mobility at data centre provider Equinix, says voice thrived and data failed in the last decade because of a set of well-established routes, which simply weren’t in place when the Enron’s of the world attempted to build a trading platform.

“Voice had a set of interconnect points and routes, and you had people in place that ran tandems or resellers who sat behind networks and it never flipped into the idea that voice was ever sold as a commodity,” he says. “Certainly, bandwidth has moved closer to voice and it is slowly beginning to reach towards a more fluid market, but I certainly do not see commercial wide adoption as yet.”

Elliott’s Band-X IP trading platform was bought out by Mashinsky’s Arbinet during a time when the stock market was highly reactionary. Any murmurings in the market that suggested activity in bandwidth trading sent stocks flying.

Mashinsky recalls that when Enron first announced its strategy for bandwidth trading, its stock doubled in value from $30 to $60. The story goes a long way to explaining why the sector collapsed so rapidly. “All they said was, we are interested in bandwidth and we are going to start playing in it. It was pretty much the same case for any other company.”

Mashinsky reveals to Capacity that Enron was not the only company that looked to Arbinet to beef up its operation. “Because of our exchange strategy, at one point before the telecoms bust we were offered $1.6 billion to go public but we never completed the transaction. Global Crossing also tried to acquire us, but its valuation was too low.”

And the potential for bandwidth trading to grow and develop was fuelled by the bigger players’ interests in the service, says Elliott. Before the collapse of 2001, the industry saw the emergence of a generation of very well-funded carrier’s carriers.

This helped create a pure wholesale network with the single purpose of selling on wholesale services. Such market dynamics played nicely into the hands of bandwidth trading because it allowed start-ups to cheaply operate in the market and acquire global network connectivity.

“Wholesale players were the main drivers to demand on the network side of bandwidth trading but a significant proportion of these went bust within the space of six months,” says Elliott.

Back then, growth came from the plethora of carriers buying capacity which was then sold on in the wholesale sphere. This inadvertently created the same fundamentals that a bandwidth trading platform is based on.

Trading thrived, says Elliott, but when the collapse hit it was almost comparable to what the banking sector experienced in 2008. “Almost $4 trillion was obliterated from the telecommunications and technology sector and almost all bandwidth trading organisations collapsed. Subsequently, we haven’t seen a bandwidth trading sector emerge ever since, until now.”

So why now? Hipp and Epsilon clearly believe its online tool will pave the way for capacity trading services on a global scale.

“Enron claimed that they could offer a differentiated service, but really they were just powering their own network under the illusion of trading,” says Hipp. “It was just too early to get the concept going. We believe we have now reached the right pricing levels and margins, with more people understanding what the service is. It’s a traditional network service that provides a point-to-point link.”

With optimism naturally comes pessimism. The market still appears at odds with regards to how responsive operators will be to such a platform.

Tom Madaras is now senior sales engineer for CDN services at Level 3, but was formerly the man in charge of global capacity at Enron and worked with a range of traders to establish the viability of an exchange platform. Madaras claims Enron’s failure was down to the fact that “carriers had established a good old boys network”.

Controversially, he says: “Carriers kept their assets close to their hearts and they didn’t want to give up any sort of control. They had built and network and decided they did not want to play with Enron, and dismissed it as a gimmick. Ultimately, we at Enron had a great concept, a great product but they couldn’t see the benefit of creating liquidity in the market and the rest is history.”

And despite Hipp downplaying the amount of risk it has taken, Poole believes Epsilon is taking on something in an industry “that is a slow beast to make changes”. He says: “No-one seems to be going out on the limb to say they will throw all their excess capacity into this. I see itinerant intermittent interest, not some saying, this is the future and I have to jump on this.”

Is bandwidth tradable?

The main issue with trading bandwidth and wholesale services is “how do you make money out of something that continuously drops in price?” says Mashinsky.

When it came to trading minutes, small incremental improvements on a voice trading platform only saved the carriers a few pennies - not big returns.

According to Mashinsky, the difference is that bandwidth is a growing business. “It will continue to grow for years and it is clear that traffic volume will scale up because the economies of the internet are going to change. In different ways, you are seeing an exchange model emerging with companies like Level 3 and Netflix paying peering premiums to Comcast for the delivery of video with Comcast dictating the pricing.”

It is equally important to remember the market’s relative infancy, according to Elliott. “Utility trading has only really emerged in the past 25 years. The centralised market for oil, gas and electricity only emerged in the late seventies so there certainly is a viable market for traded bandwidth. I spent a good number of dollars trying to perfect it with Band-X.”

Drawing on his past experiences with Eron, Madaras believes there are still potential limitations with the bandwidth exchange model in today’s marketplace. Namely, that the number of companies which control the physical assets remains small.

“Bandwidth still isn’t at the point that it can be physically traded,” he says. “For all the price compression that has occurred in the market, the number of companies that control it on any given route is small. In some ways it is utilised as a commodity in the metro markets. On long-haul routes, which are already established in developed markets like the Americas and western Europe, the paradigm is the same. People who control those routes are still trying to manage prices as closely as they can.”

This differentiates bandwidth from the real lifeblood of tradable products, like commodities or stock, where there are an insurmountable number of players investing, trading and interacting. “It’s still sitting in very few hands and if you want to trade in real volumes you need liquidity,” he says.

“For this platform to really work you need big players like AOL, Amazon, Netflix and Google to enable this capability for customers. If Amazon cloud or Amazon video services started to buy capacity through this exchange this will blossom. Unfortunately, sellers do not want liquidity or transparency because that will mean a price drop, and buyers will have the ability to switch to the cheapest sellers efficiently.”

In some ways, the entire premise of an online trading exchange platform actually goes against the fundamentals of wholesale telecommunications, which prides itself around the idea of networking and holding good client relationships.

“Friends do business with friends, but that’s the problem,” says Madaras. “If we continue down that road it will never allow for liquidity and yes, people do business with people they know but we need to move away from that world.

The time has come for an international body to set regulations on how business is done, develop a costing and interconnect model to create a standard playing field for everyone.”

Breaking barriers

Aware of the industry’s perception of bandwidth trading platforms, Hipp urges his fellow colleagues to embrace change. “People have even spoken to me about the impact this sort of thing will have on jobs, but it’s not something we should fear,” he says. “The earlier companies address where the market is going and prepare for lower margins, the more time we have to prepare for it.”

For Mashinsky, the memory of a failure to establish bandwidth trading has long lingered in his mind. He notes that Arbinet’s IPO in 2004 was the highest that year, beating Google which also went public. He clearly still carries regret when discussing his past with

the company.

“We never took off after going public, and continued to fall below Wall Street expectations. In the end they began to focus on international voice. I moved on to other things [now founder of VC technology company Governing Dynamics] but did try to convince the board that I should be reappointed CEO in 2007. The ‘geniuses’ at the board opted to hire middle management from mediocre companies. It’s very painful when it’s something that you have created and nurtured, then have to watch it get yanked away and suffocated.”

Why did Enron fail?

Enron filed for bankruptcy in late 2001 and it is a widely held view within the market that its failure to establish a trading exchange platform was a major proponent to its collapse.

Although the service was relatively small in contrast to its interests in commodities and energy, the company invested aggressively in developing the business to sit beside its energy products.

Here, industry experts offer contrasting views to why the company failed over 11 years ago:

|

| Richard Elliott: | |

|

|

| Alex Mashinsky: |

|

|

| Andreas Hipp: |

|

|

| Tom Madaras: |

|

|

| Jim Poole: |