It’s quite feasible that, within a few years, there will be tens of thousands of low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites in operation around the planet, orbiting between 550km and 1,200km above our heads. Most of them, on present trends, will be Starlink’s, owned by Elon Musk’s SpaceX, but others are jumping into the business, though on a more modest scale. It makes you wonder how many can survive.

The market so far features, as competitors to the Musk in Space Show, six companies: OneWeb, rescued from oblivion in 2020; Lightspeed, being brought into life by Canadian operator Telesat; Project Kuiper, Amazon’s own LEO scheme; Inmarsat, which wants to launch LEO satellites as part of its Orchestra network; Boeing, which applied for a LEO licence in October 2021; and China’s own Guo Wang, about which little is so far known.

SpaceX and its Starlink are way ahead. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has already approved 12,000 satellites via the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) – and SpaceX wants 30,000 more.

According to a Cambridge Wireless conference in November 2021 – hat-tip to Dean Bubley for posting details on Twitter – Guo Wang has filed a licence application with the ITU for 12,992 LEO satellites. OneWeb’s first fleet, most of which is in orbit already, will have 648 satellites at 1,200km. The rest should be in service by mid-2022.

Amazon has a licence for 3,236 Kuiper satellites, of which half should be in service by 2026, the rest by July 2029. It plans to orbit two test satellites by the end of 2022.

Fibre-like network

The most recent arrival – at least, the most recent to provide details – is Telesat, which has merged with fellow Canadian operator Loral to facilitate the process. It plans 298 interconnected LEO satellites “coupled with a sophisticated and integrated terrestrial infrastructure to create a fibre-like broadband network from the sky for commercial and government users worldwide”, as it told the US financial regulator in November.

Inmarsat’s plans, announced in July 2021, are for a future LEO constellation in the range of 150-175 satellites, integrated with the company’s long-standing geostationary satellites and a new terrestrial network, Orchestra. Though one must suspect that these plans might be coming under scrutiny if the proposed $7 billion merger with US-based Viasat, announced in November 2021, goes ahead.

The companies say they are going ahead, but plans have a habit of changing when a new management team comes on board – and remember that Inmarsat’s existing CEO, Rajeev Suri, joined as recently as March 2021, so even he was new to the game.

I know of at least one more, but I was told confidentially. When and if I can, I will add that – and any others – to the list.

Let’s get out that spare envelope and add these numbers together, assuming that the respective CEOs’ optimism holds out.

Amazon, Inmarsat, OneWeb and Telesat between them plan 4,300 satellites. Guo Wang gives a remarkably precise number, so add that and you get 17,000. And then SpaceX’s Starlink? Well, how big is Elon Musk’s ego: no, don’t answer that, but if he gets a decent percentage of his ambition, let’s say there will be a total of 50,000 LEO satellites from all operators in service by the end of the decade.

The surface area of the Earth is just under 500 million sq km. That means there will be one LEO satellite on average per 10,000 sq km – or, in other words, one satellite for every theoretical square of 100km sides.

Crowded space

Yes, I know there’s vertical separation too – a maximum of 600km or so between the highest and the lowest, and they are all moving in different directions and at different speeds – but I hope you get the point. It will be crowded up there.

The arrival of LEO will be as complete a change for the satellite industry as, say, the arrival of fibre meant for the subsea business, or as cellular was for the plain old phone business. Suddenly there will be vast amounts of capacity just above our heads.

How much? Starlink is talking of 17Gbps per satellite; OneWeb about 7.5Gbps. The two later arrivals will do even better: 30Gbps for each of Amazon’s Kuiper satellites and 50Gbps for each Telesat Lightspeed satellite.

By modern standards that’s not a vast amount. If I could get a fibre to deliver 1Gbps to my home, and half a dozen of my neighbours could do the same, between us we would have more capacity than a single first-generation OneWeb satellite. Of course, I would rarely use 1Gbps, even if it were available, and all users share capacity, whatever the theoretical peak rate is for each of them. But this means LEO is ideally suited to low-density rural areas.

By their very nature, satellites are global. You can’t just orbit round and round Canada, or round and round China: once you’re up there, you’re forced to go all round the world, so where you offer service comes down to where you can negotiate licences with the local regulators. Operators will, in theory, be able to switch beams on and off as their satellites pass over.

Back to the ground

And they will all require uplinks and downlinks to connect them to the rest of the world’s digital networks. For a satellite 500km up, the horizon is about 2,500km away, so a single Starlink satellite will need a ground station within that range. And, as it moves at a speed of around 8km a second across the planet, another a few minutes later, and again.

It’s better for OneWeb satellites, whose horizon is 4,000km. But that still demands a profusion of ground-based satellite stations, while the old GEO satellites could more or less get away with one for each of the planet’s hemispheres.

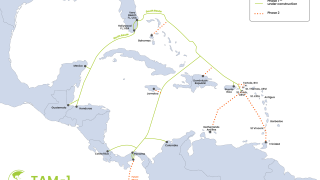

This is why the latest innovation – interconnected LEO satellites, which Telesat is promising and which others have hinted about – is intriguing.

If traffic can hop from satellite to satellite, in theory you can offer service where you’re not licensed and where you have no ground stations. This could, potentially, open the way to borderless services – a ground station in, say, Italy or the US could drop traffic into and out of Afghanistan or Sudan or anywhere. Expect a fight, though, with regulators and licensed operators.