Full restoration is waiting on the arrival of the cable ship Reliance, owned by Subcom, which is on the way. It has to call first at Samoa, where stores are kept on behalf of all regional cable operators, before heading to Tonga.

According to Shally Jannif, regional CEO of Digicel, one of the biggest local operators, Reliance should dock in Samoa “at the weekend” before heading south to Tonga, where it is expected to arrive by next Thursday.

Fortunately Digicel Tonga’s network operations centre (NOC) is on some of the highest ground on the main island, Tongatapu, and escaped any damage from the tsunami that followed the huge 14 January eruption. (See picture, from the US NOAA.)

“Our team had enough time to get there,” she told Capacity from her office in Australia yesterday. “The NOC was above the tsunami: we built it on the highest point available.”

Tongatapu has 70% of the country’s population, including residents of Tonga’s capital city, Nukuʻalofa.

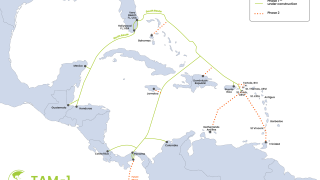

On arrival, cable ship Reliance will first focus on the 827km Tonga Cable, which runs from the Fintel cable landing station in Suva, Fiji, to Sopu, Tongatapu, which carries all of Tonga’s fixed international connection, and 90% of Tonga’s traffic.

The domestic cable, which links Tongatapu to two outlying northern islands, Neiafu and Pangai, is 410km long.

“The international cable break is approximately 37km offshore from Tonga,” said Digicel shortly after the eruption. Physically the two cables are close together where they are both broken.

But no one knows how much damage either cable suffered – not just from the volcano, but also from the landslips that will have resulted.

“A landslip is also likely to have moved the cables,” said Ranulf Scarbrough, CEO of Avaroa Cable, the company that connected the Cook Islands to the Manatua One Polynesia cable in 2020.

The cables are broken in sea that is between 1.5 and 2km deep, he added: meaning that the Reliance crew will need to splice in a good length of extra cable, even if there is a clean cut. But if cable is buried or damaged, potentially much more will be needed.

One subsea cable expert told us: “The duration of a repair depends on numerous things – type of fault, depth of water, cable type, buried or unburied, the length of the system damaged, and of course, the prevailing weather conditions.”

This person, who works with a number of subsea companies so did not want to be named, said: “For a simple fault – a single cable break – a period of seven days on site before the cable can be put back into traffic is typical.”

But “the problem with an underwater eruption and subsequent tsunami is that long lengths of cable can be damaged buried or swept away. The more damage there is the longer the repair will take.”

Jannif confirmed: “We’re expecting the damage may be large.” She expects repairs to the Tonga Cable alone might take “two to three weeks” from Reliance’s arrival on site next week.

Tonga has experience of cable cuts. In January 2019 a ship, which has been identified, dragged its anchor over the Tonga Cable. “It took about a week to repair,” said Jannif – and that was once the repair ship had arrived on site.

Until Subcom’s Reliance can turn its attention to the Tonga Domestic Cable Extension, telecoms operators are hoping to rely on microwave links between the islands – but the force of the volcano has knocked them out of alignment, Jannif told Capacity.

Technicians need to be flown in by helicopter, including to one site on an uninhabited island, to realign them.

The whole situation has been “an eye-opener”, she said, as the volcano was an unexpected event. “We have plenty of cyclones to plan for. This is supposed to be cyclone season,” said Jannif.

Now, she says, operators, governments and regulators in the area have to plan for such incidents, “especially with climate change. We can only expect things to get worse.”

Some islands – but not Tonga – have more than one cable, but usually there is one cable landing station per island, meaning there is no resilience in case of a tsunami following an earthquake or volcano.

And it is expensive to duplicate cables for a community with a small population. The Cook Islands connection cost about US$25 million, funded by ultra-low interest loans from New Zealand and US development agencies.

“The economics is a big challenge,” said Scarbrough. Commercial funds would attract interest rates of 15-20% a year – up to $5 million shared between 105,000 people: nearly $50 per head of population a year before any local infrastructure.

Satellite services, including Intelsat and SES, have helped to restore services, and companies will need to build them into their plans for future resilience.

The Cook Islands have access to SES’s O3b satellites, which are medium Earth orbit (MEO), providing low latency – almost imperceptible compared with traditional geosynchronous satellites.

That would appear to be the way forward for operators wanting to protect their international connections. Disasters will cut cables from time to time: satellites are essential if operators and governments want resilience. Jannif is keeping a close eye on Vanuatu, where another volcano has become active. “This has to be an industry-wide issue,” she said.