Luis Fiallo has a major job on his hands: to rebuild the business of the US operations of China Telecom when it’s no longer allowed to run telecoms services in the biggest business market in the world. China Telecom Americas (CTA) is the offshoot of the state-owned, Beijing-based China Telecom. It’s been around a long time.

“Last year we were celebrating 20 years in the US,” Fiallo tells me, sitting in the US hotel where in May Capacity held International Telecoms Week (ITW).

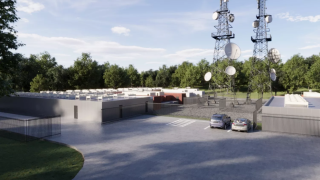

The company’s headquarters is at Herndon, Virginia, in that cluster of telecoms companies – Arelion, PCCW Global and the others – snuggled along the toll road from Dulles Airport to the centre of Washington DC.

CTA’s main office is just under 20 miles from the White House. And it’s the White House where CTA’s problems started, when at first president Donald Trump and then his successor, Joe Biden, set their face against Chinese carriers and Chinese vendors. Nothing was, or has been, proved publicly, but first Washington spurned vendors such as Huawei and ZTE, and then turned to Chinese carriers.

The Trump administration issued executive orders attacking the carriers.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) refused to give China Mobile a licence to offer services in the US, and then announced it was withdrawing licences from China Telecom, China Unicom and subsidiaries of CITIC Telecom. The Department of Defense said they were a security risk. They lost their listing on the New York Stock Exchange.

And then, as Biden took over in early 2021, his FCC – led by Jessica Rosenworcel as chairwoman – continued the policy that began under Trump.

Fiallo is not taking this legal activity quietly. “We’re appealing,” he tells me. “We’re invoking our rights. We’re a good company, and 70% of our employees are American citizens. We’ve invested a lot of money in infrastructure and security. We have a very robust security team.”

But he has faced reality. The “Americas” in CTA’s name is more than just the US. CTA is still working in Canada. “We have a robust business there,” Fiallo says.

The company is already in some places in South America too, “and in the next couple of years we plan to expand to all South American countries,” he says. “Mexico is on our horizon and we are trying to understand Central America a bit better.” The Caribbean? “It has a limited customer base,” he shrugs.

But, he admits ruefully, “the buying power of the US is totally different.”

A quick check shows that the combined gross domestic product (GDP) of Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, Chile and Peru is US$3.5 trillion a year; the GDP of the US is six times that, at $21 trillion. Even with Canada’s $1.6 trillion GDP, the addressable market is just a fifth of what it could be.

Out of bounds

But now the US is out of bounds to CTA, at least in terms of regulated telecoms services. However, there are alternative services that CTA can still provide in the US, because they are services that don’t require a licence from the FCC.

That brings us to the reason China Telecom is in the Americas in the first place. “When the company set up [in the US] it was designed to help the China Telecom group, and we picked the most competitive market in the world.”

It’s 17 years since Fiallo joined CTA, having earlier worked for BCE Teleglobe, which later became Tata Communications, and then been an independent consultant. CTA “started off to help American companies go to China, in the early 2000s, helping them do business in China and teaching them how to get involved in China.”

Remember, this was a period when the Chinese economy was starting to expand rapidly. Western companies wanted to sell to China, and to buy from China. That meant they needed communications services between the US and other western economies to and from China.

“I’ve been able to see the success of the Chinese market,” says Fiallo. Even before he joined CTA, he was partnering with the parent company in the 1990s to build a data centre in Pudong, Shanghai.

CTA moved from its initial approach of working just with carriers to “helping US multinationals work in China” – not just China Telecom, but other Chinese operators too.

And then in 2007-2008, Fiallo recalls, “we saw Chinese companies coming out” to the rest of the world, so CTA found yet another role – helping those enterprises work in the West. “Chinese companies wanted to come to the Americas,” he says.

There’s another angle to what CTA has done over the years: work with internet service providers in Brazil, where it now has 11 points of presence in the southern part of the country. “We went to the ISP community, achieving double-digit growth”, he says, and connecting a maximum of 8,000 ISPs.

CTA was ready to expand to Panama and Mexico when Covid hit. But it’s continued with its role as an aggregator of traffic on the China-Americas service, except for Brazil, where traffic is more internal.

Latin America

“What we started to do was look at opportunities in Latin America. The world is moving to the cloud and everything is about computing power,” says Fiallo.

“We decided to focus on an overlay network. We started to do that in the US, getting people to the cloud and data centres.”

Fiallo emphasises that CTA “never built a network in the US”. Instead, “we leased capacity from half these guys here”, he says, looking through the hotel window at the milling crowds at ITW.

The China Telecom group “is one of the largest owners of capacity between the US and China”, Fiallo says. The network connects “40 metro locations across the world and 80 cloud locations across the world. And we have our own cloud infrastructure.”

The company connects to “all the cloud companies”, he adds, listing AWS, Google and Microsoft as well as Chinese cloud services such as Alibaba and Tencent. “And in China it helps that we can use our parent company’s resources for the last mile.”

He turns back to the Latin American market. “Brazil’s the largest, then Mexico second.” After that he lists Argentina, Chile, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia. “We’re building the on-ramps to data centres or to actual cloud partners that they need. That’s our renewed focus.”

Back to the FCC: Fiallo is reluctant to say too much. Capacity wasn’t ambushing him – when we arranged to do the interview at ITW, his PR consultant said: “Fair enough to ask about the licensing with the US.” Indeed, if we hadn’t discussed the major issue facing CTA in 2022, the interview would have been meaningless.

“We are compliant,” he insists, referring to section 214 of the Communications Act of 1934, which governs all foreign-owned operators in the US.

Yes, it really is 88 years old, passed into law when Franklin Delano Roosevelt was just months into his first of a record four terms of office (FDR didn’t complete the fourth; he was inaugurated in January 1945 and died a few months later). When that Act was passed, international telecoms meant telegrams and some telephone calls into Canada and Mexico and via radio to Europe.

Legal processes

Though Fiallo says that CTA is appealing against the decision, the legal process appears to have been exhausted. In March 2022, the FCC told the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit that “although China Telecom received appropriate opportunity to demonstrate or achieve compliance with the relevant requirements to hold Section 214 authorisations, it was unable to show that there were any further measures it could take that would mitigate or cure the serious national security and law enforcement concerns that the commission identified.”

Fiallo says: “We’ve stayed doing all the things we don’t need a licence for. We continue to serve the same people. US companies wanting to go to China need equipment.” And there’s the rest of the world, he says: the world that isn’t the US.

Has the FCC’s action – which was backed by both the Trump and then the Biden administrations, remember – hurt CTA? On this, Fiallo kept his lips tightly closed. That’s a question he won’t answer.

“Our bread and butter is solving problems,” he says. “We know how to do business in China. China Telecom is a leader in the Internet of Things and 5G. We are able to use technology that moves video faster.”

The company is, he adds, “extending the edge in Latin America, to be able to bring this [data] back to the core”.